You know what it's like now: a lot of exciting bands are getting their first release on tape. Things were a little different in the late 80s.

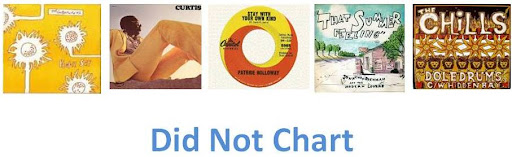

The photo shows some of the tapes I bought (and, in one instance, was sent free) between 86 and 89. In the indiepop scene then, there was a format war. This centred on 7" singles being idealised both aesthetically and economically, with a concomitant hatred of 12" singles.

This skirmish manifested itself most playfully in the Sha-la-la label, who released six-and-a-half-inch flexidiscs so the listener couldn't use a record player's auto-return and had to physically interact with the record for each play.

The cheap and disposable ethic of flexidiscs was an extension of the tape scene, which was an incredibly important part of the post-punk DIY movement. Tape culture embodied punk's ethos of being cheap and easy, only more so: they were even cheaper and easier to record and release than vinyl.

That episode in cassette history was strongest in the early 80s. From about 1986 onwards, compilation tapes became really useful in hearing those bands you'd read about in fanzines or kindred spirits to bands you already liked.

It was incredibly difficult back then to hear unreleased bands or even bands who had a record out. Unless John Peel played a demo tape or you stumbled across a new band at a gig, or you lived near a cool record shop that stocked the pop underground releases, you just couldn't hear a lot of new music.

Compilation tapes were vital in the indiepop scene back then. Look at that photo. There's Like Flies In The Face Of, an essential round-up of the Australian pop underground; there's Akko-Chan's Anorak Party, compiling the Japanese scene; and there's Something's Burning In Paradise, which had hit after unheard hit.

Then, like now, there were new bands with cassette-only releases. Keen I found out about from a compilation tape and bought their own tape. They later released two records. Similarly, Emil I discovered through a compilation tape. They released one tape ep and that was the end of that.

There's a collection of St Christopher demos there. I bought that on mail order from the band. All money went their way. At that point they'd released three (self-funded) singles and a flexi in four years. Maybe that's something for downloaders to think about next time they grab music they could otherwise buy.

Primal Scream? There was a stall in Camden Market that could meet most of your bootleg needs. It was the only place to find Tomorrow Ends Today. Of course, if then were now and it had been uploaded, then I'd have rather bought a download from the band than line the pockets of a market stallholder.

The Cannanes had a catalogue of records and tapes. An album-length tape could be had for less money than an import 7". It made sense to the 13-year-old me.

The Shop Assistants? It was in the sale. The last tape I bought when there was a vinyl alternative. Again, this was economic.

The Telescopes? Their first demo and some live recordings. I used to correspond with one of the band members because she wrote a fanzine. She sent me that free, along with some pointers to music new to me.

Why am I describing each of these tapes? Because tapes tell stories; MP3s don't.

Naturally, I'm delighted that in 2012 there are so many great new bands getting their music out on a physical format. I'm not calling out any of these bands or their labels as hipsters; though I don't doubt that's the motive for some, I don't believe it's the inspiration for any of the music I buy.

Records are expensive to buy. In the past decade, the price of 7"s has rocketed, not least due to the unfortunate ebay culture and some labels marketing them as fetishistic objects with inflated collectors' prices.

I know some people who run record labels are losing money hand over fist by releasing records to a dwindling record-buying public. The audience is there, but the money from that audience isn't.

I don't expect that a tape release will ever sell as many as a record would, but a tape sure as hell won't lose the label or band money like a record would. Economies of scale dictate that the smaller the pressing run, the more expensive the record. The more expensive the record, the fewer potential buyers and the more money the label loses.

I don't love tapes. But if it's the only way for bands to get a physical release without them or their label going bankrupt, then I'm onside.

No comments:

Post a Comment